Session 21: presentation

| Session | 21 (2011–2012) |

|---|---|

| Participants |

Albertine de Galbert |

| Direction |

Yves Aupetitallot |

| Session website | |

| Coordination |

Lore Gablier |

| Tutoring |

Fareed Armaly |

| Educational team |

Tolga Taluy |

| People met |

Naïm Aït-Sidhoum |

| Travels |

Berne, Genève, Kassel (dOCUMENTA), Lyon, Genk-Limburg (Manifesta), Paris, Zürich |

Related archive

Documents

- Programme cycle de conférences : la question de l’exposition de l’image photographique [pdf, 489.95 KB]

- session-21-premise-reader.pdf [pdf, 54.63 KB]

Media and links

Photographs

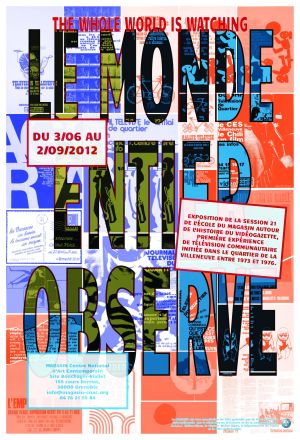

The Whole World is Watching

| Project |

The Whole World is Watching |

|---|---|

| Presentation |

The Whole World is Watching stems from research into the history of Vidéogazette (1973-1976), a collective of activists and technicians who taught citizens in the newly built suburb of Villeneuve, Grenoble, how to use audiovisual equipment and produce their own television channel. In the early 70’s, Villeneuve and its experimental urban plan presented a model of co-habitation and communal life that attracted activists and filmmakers. Modelled after Vidéogazette’s broadcasting studio “Agora”, The Whole World is Watching transforms MAGASIN’s auditorium into an exhibition space and brings together a selection from the Vidéogazette print and video archives with a series of related video works Together, the works offer multiple points of entry into the collective space defined by technology in its contrasting characteristics: a self-determined community where individuals join together, a cacophonous collection of isolated and atomised voices, a territory claimed by centralised corporate and State power, and a laboratory for possible future scenarios. |

| Format |

Exhibition and website |

| Date |

3 June – 2 September 2012 |

| Location |

Auditorium, Magasin-CNAC |

| With |

Pierre Bismuth |

Related archive

Documents

- Dossier de presse (FR) [pdf, 2.7 MB]

- Press dossier (EN) [pdf, 353.44 KB]

- Presentation of La Villeneuve [pdf, 7.03 MB]

- Presentation of the project - December 2011 (EN) [pdf, 1.41 MB]

- Brochure d’exposition (FR) [pdf, 213.46 KB]

- Contribution by Pierre Musso, ‘Les réseaux amplifient l’action socio-politique, mais ne la remplacent pas’ (FR) [pdf, 280.96 KB]

- Histoire de Vidéogazette (FR) [pdf, 361.18 KB]

- Contribution by the collective Journal of aesthetic and protest (EN) [pdf, 899.92 KB]

Photographs

With Corrado Salzano

Interview with Corrado Salzano

by Damien Airault

05.07.2022

Damien Airault: How did you hear about the École du Magasin? What brought you there?

Corrado Salzano: from Italy and I worked between Turin and Milan, in a few institutions and galleries. Then I moved to Amsterdam and probably got to know a few people at De Appel, so I probably started looking for curatorial schools. There was De Appel, which I couldn’t afford, and the Magasin was free, so the problem was only how to stay in Grenoble, not how to pay for the program.

DA: You were quite old when you entered the Magasin.

CS: Yes, I was 29.

DA: What made you decide to go there? What were your expectations?

CS: Previously, I had worked mainly as a curator assistant or a gallery assistant. I saw that Le Magasin offered the possibility to do a project on your own. You had a framework in which you could build your own project and learn by doing.

DA: Did you graduate in art history?

CS: I graduated not in traditional art history, but in this Italian faculty founded by Umberto Eco. 1 It was a sort of semiology course. The core was semiotics and it was applied to theatre, music, cinema and art. So it was interdisciplinary and you would “pick” your spot. I picked contemporary art. It was not classic art history.

DA: Do you remember your interview in Grenoble?

CS: There was the director of Le Magasin [Yves Aupetitallot], Lore [Gablier], and Tolga [Taluy]. They asked me to prepare an exhibition proposal along with a CV. My proposal was inspired by an exhibition I saw at De Appel, I’m Not Here. An Exhibition Without Francis Alÿs, which took place in April-June 2010.

DA: What was the schedule with your tutor, Fareed Armaly?

CS: He came early on to kick off the year, and then, he came back maybe once a month. In the beginning, there was a kind of “incubation period” so he came for a whole week, and then we were in touch by email. Afterward, he came back once a month. I think he came for the opening of the project as well.

DA: Were there other permanent collaborators or tutors?

CS: No, there was Lore and Fareed.

DA: It was changing almost every year… Was it possible to invite some people of your choice to come to Grenoble?

CS: We had a budget but we used it mainly for traveling, for example, to Switzerland. For sure, we were in touch with students from the art academy in Lyon.

DA: I know you went to Kassel as well.

CS: Yes, as well as to Manifesta in Genk, but it was at the end of the year.

DA: I supposed that to build your project, The Whole World Is Watching, you also met people. But did you also meet people who would give you skills or courses on history, economy, contemporary art, etc.?

CS: No, there was nothing like that.

DA: Wasn’t there anyone to give you things to read or texts to write, exercises or mini-seminars?

CS: Fareed had a little bit of this role. He gave us some inputs, made presentations and, right from the start, we would share and read a text, talk about it, and write something to send back to Fareed. The whole thing was about discussion, and his role was to give us some input.

DA: And this thing about Walter Benjamin comes from you or from Fareed? Because it was also a big reference ten years before.

CS: No. Walter Benjamin was just the first quote we took about technology. I don’t think it came from Fareed.

DA: Did you have contacts with people in the art centre? Did you have to work with the staff, or maybe they had to present their jobs? Did you have friendly relations with them?

CS: Yes, we were in touch with the team.

DA: I am trying to understand what was the “sociality” (in French we say “socialité”) of the students: How did they survive in Grenoble, make friends? Who did they spend their evenings with Have you made any friends, for example with art school students? How did you build a network in Grenoble, if you did at all?

CS: I can only speak about my personal experience. in the evenings, I worked at La Bobine. It’s a club, an associative cultural centre. I was a barman. I got to know a bit about that community and that’s how I was able to support myself financially. As soon as I arrived in Grenoble, I started couchsurfing. I immediately met Arbresha, a Kosovar-French girl, and we became good friends actually. Then I got a house in the centre of the city with flatmates. We were also spending time together with the other colleagues, and met former students of Le Magasin as well. I remember Tolga was around, for instance.

DA: It’s quite interesting because you’re the first student I’ve interviewed who’s had a real job outside Le Magasin while studying. And I know that the city became very expensive at that moment. Ten years earlier, it wasn’t so expensive. Perhaps most of the students had their flats paid for by their parents or had a small grant, or, at some point, weren’t living in Grenoble, which happened a lot.

One of the École’s ambitions was to set up a professional network. Have you managed to do that a bit? How were you introduced to this? Did someone say to you “You must meet this important person”? How do you feel about this? Because it’s a very strange thing for me.

CS: For sure, we met people from the local scene. There was this art space at La Bastille as well as a small art centre run by artists, so we met local art venues. We went to Lyon where we met one of the curators of Documenta, Chuz Martinez. We went to Paris and visited the FIAC and La Maison Rouge, which was the art space founded by Albertine’s father.

DA: Let’s speak a bit about your project. Do you remember how the idea of working on Vidéogazette came up?

CS: There were two points of interest. The first was La Villeneuve. It was 2012 and a few years earlier there had been this story about a guy from La Villeneuve who I think had tried to rob a casino and got away, and the police shot him. And in Villeneuve, there was a big riot, people started burning cars. This happened even before the riots in the Paris suburbs. At La Villeneuve, there were many people with a migration background and the Minister of the Interior, Sarkozy, came to Grenoble and gave this speech saying in essence: “I don’t care if you are third or fourth generation immigrants if you don’t deserve French citizenship, we’ll take it away from you.” The press then reacted by describing the Villeneuve as a sort of “crazy ghetto”. Somehow, I was interested in the way the Villeneuve project started as a kind of pragmatic municipal socialism: a place for communal living. It was described this way. What was interesting was to do some justice to this place, to its origin, to the original idea, against this type of media representation. So there was a great fascination with the story of La Villeneuve. It’s also because there are so many places in Europe that were born out of this idea of communal living, with this modernist rationalist architecture, which became problematic over time. That was the first point of interest.

The second point concerned Vidéogazette itself. It was a rather striking history, one of the first experiments in local television, in the early 1970s, when there was only state television. It was also one of the first experiments with portable cameras and so on. It was very interesting in itself because it was a group of technicians or activists who basically organised workshops, for instance with kids at school, and their idea was: “We’ll teach you how to use the camera, you’ll make your own programs, then we’ll broadcast it in a shared space during the evening and we’ll discuss important issues for the neighbourhood.” At some point, there was a local cable so it became possible to also broadcast in the department. This was quite striking historically. And in 2012, there were all these movements like Occupy Wall Street, the Indignados in Spain, there was even this big question mark of the Arab Spring. So it was a question of how the new generations were using new technologies, cameras, smartphones, and social media, to organise politically. The local experiment of Vidéogazette resounded with these contemporary events. We wanted to draw this line, this parallel. And of course, we were an international group living in Grenoble and we were interested in how this local history could connect with other international events.

Anyway, these were the two main points of interest: the history of La Villeneuve and the history of Vidéogazette itself.DA: Did you meet everybody? Did you manage to see the videotapes and to show them? If I’m right, you presented an exhibition in the auditorium. Was there a publication or a book about Vidéogazette? You were kind of the first to study this channel!

CS: An exhibition was organised previously at Le Magasin but it had a different focus. 2 It was about Grenoble and the artists who lived there in the past. For example, this exhibition showed Godard in Grenoble during the 1970s. It was also showing a video from Vidéogazette, because one of the school kids who took part in the Vidéogazette’s workshops was Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster. She grew up in La Villeneuve and she was in one of these videos. The exhibition showed it, saying that this has happened, so Vidéogazette was one among many elements. We saw that and decided to focus our project on this history.

DA: Was this exhibition part of the programme of the art centre?

CS: Yes, it may well have been curated by the director, Yves Aupetitallot. Anyway, we basically had the videotapes and we found the local archives in Grenoble: a lot of flyers, leaflets. Vidéogazette lasted a few years, but then the funding was cut so the people who were working there left Grenoble. We managed to get in touch with one of them who was living in Nantes. He was the graphic designer of Vidéogazette. His name was Patrick Di Meglio. This was probably Lore’s masterpiece: she managed to get in touch with him. So we got this amazing archive of posters.

DA: Yes, I’ve seen three interviews with people from Vidéogazette: Denis Requillart, Jean Leclerc and Patrick Di Meglio. It was a small exhibition. I saw that the budget was around 5000 euros.

CS: We did an exhibition and a website.

DA: Did your opening take place during the opening of the Magasin’s main exhibition?

CS: Yes, I think it was an exhibition by Isabelle Cornaro.

DA: What do you think of your exhibition ten years on?

CS: I reread today the things we wrote on the website and I think it was a good project, even if not everything was developed or perfect.

DA: This exhibition also reflects the style of the École, with lots of documents and information. At De Appel, we would say that this is an exhibition of the “pedagogical turn” and it is very symptomatic of this period.

CS: For me, it’s important to provide proper information in the exhibition, so as not to assume that the public knows the context. It’s always important to put something down on paper and give background information, otherwise the exhibition is only aimed at a specialist audience and not a general one. Of course, if there’s too much text, it kills you. I don’t think we needed too much writing with that exhibition. There was a leaflet and we put the written part on the website, so if you wanted to find out more, that was possible, but we didn’t put it all in the exhibition.

DA: I didn’t see that.

CS: Basically, we had a table with a screen on which the website was displayed, and the texts were simply presented online.

DA: How did you build the show? Did you determine tasks, competencies, did you try to separate out all the things that you had to do? How did you organise?

CS: Sarah [Sandler] was an architect by profession, so at a certain point, she took over the scenography and the build-up. Shoghig [Halajian] was very good with planning and communication, while I was a little bit more into the writing part.

DA: How was your relationship with Lore [Gablier]? Was she after you, did she give you deadlines or leave you free? You were also quite old students, all “grown-up adults”, and perhaps you didn’t need anyone to set up your agenda…

CS: She knew all the people in the organisation. She also knew the context because she comes from the region, and of course, she was the one who spoke French, even though I started speaking French at a certain point. For example, she was super important to get in touch with the people from the Vidéogazette and to support us.

DA: This interview is almost finished. Do you have anything to add? How did the École help you in your career?

CS: For me, it was quite an amazing experience, like a project in itself. For the rest, I do not work in the art world right now. I work as a coordinator of events for a fashion brand in Berlin. I organise workshops, seminars, and training. Right after L’École du Magasin, I worked in art for a few years. I did research for the University of Warwick. I was living in Amsterdam, then I went to the UK, then I went to Belgrade where I curated a show, and then Berlin. At a certain point, I stepped out of art. I will never speak badly about the art world but there is a big problem: too many people want to work in art while there are too few jobs, so there’s a lot of exploitation, underpaid, not-paid jobs. For me, the Magasin was an important experience in life.

DA: I see what you mean.

- ndt. Corrado Salzano refers to Dams (Department of Art, Music and Entertainment) which was founded at the University of Bologna in 1971. Umberto Eco was one of the first to join the department and was appointed to the chair of Semiotics. ↩

- Corrado Salzano refers to the exhibition, Cinéma(s), which was organised in 2006. ↩